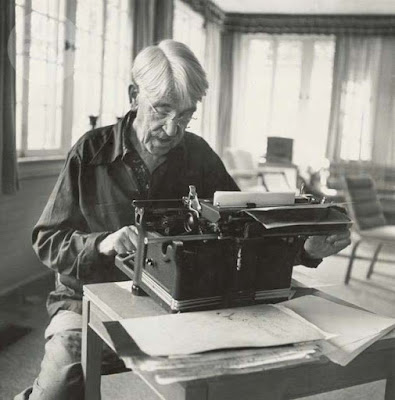

John Dewey at his Marxian and democratic best

Hilary Putnam shares a passage from John Dewey at his

Marxian and democratic best:

“Dewey’s social philosophy is not simply a restatement of

classical liberalism; for, as Dewey says, the real fallacy of classical

liberalism [a fallacy which persists with vengeance in neoliberalism]

‘lies in the notion that individuals have such a native or

original endowment of rights, powers, and wants that all that is required on

the side of institutions and laws is to eliminate the obstructions they offer

to the ‘free’ play of the natural equipment of individuals [if you will, the

‘libertarian fallacy’]. The removal of obstructions did have a liberating

effect upon such individuals [e.g., the bourgeoisie and the nobility, including

declassed aristocrats, with some trickle down and spillover effects on some

members of the lower classes] as were antecedently possessed of the means,

intellectual and economic, to take advantage of the changed social conditions,

but left all others at the mercy of the new social conditions brought about by

the free powers of those advantageously situated. The notion that men are

equally free to act if only the same legal arrangements apply equally to

all—irrespective of differences in education, and command of capital, and that

control of the social environment which is furnished by the institution of

property—is a pure absurdity, as facts have demonstrated. Since actual, that

is, effective, rights and demands are products of interactions and are not

found in the original and isolated constitution of human nature, whether moral or

psychological, mere elimination of obstructions is not enough. The latter

merely liberates force and ability as it happens to be distributed by past

accidents of history. The ‘free’ action operates disastrously as far as the

many are concerned. The only possible conclusion, both intellectually and

practically, is that the attainment of freedom conceived as a power to act in

accord with choice turns upon positive and constructive changes in social

arrangements.’

We too often forget that Dewey was a radical democrat, not a radical scoffer at

‘bourgeois democracy.’ For Dewey the democracy that we have is not something to

be spurned, but also not something to be satisfied with. The democracy that we

have is an emblem of what could be. What could be is a society which develops

the capacities of all its men and women to think for themselves, to participate

in the design and testing of social policies, and to judge results.” — From

Putnam’s Renewing Philosophy (Harvard

University Press, 1992): 199.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home