Thursday, December 15, 2011

George Whitman: communist, utopian, and humanist…and “the most un-phony person” (Update, Dec. 16)

From the Los Angeles Times obituary:

“George Whitman, the legendary founder of the Paris bookshop and literary institution Shakespeare & Co., died Wednesday. He was 98.

The Left Bank bookshop was closed Wednesday, and a note on the door said Whitman had suffered a stroke a few months earlier. He ‘died peacefully at home in the apartment above his bookshop,’ the letter said.

On Wednesday night, people stopped to leave notes, flowers and candles along the ground and covering the window of the shop, now run by his daughter, Sylvia. Many of them said the place had always been much more than a bookshop to them, but a second home. Literally.

Over the years, Whitman has sheltered about 50,000 young, struggling writer types for free, right in the shop if they needed a roof, wanted to save a franc, or just had ideas about books and a hankering for a certain bohemian way of life. All they had to do in exchange was work a few hours in the shop, write a one-page biography and provide their picture (an idea born out of Whitman’s attempt to appease French authorities who wanted to know more about the clandestine ‘hotel’ he was running on the left bank of the Seine River).

The shop has kept all the letters from past boarders, dubbed ‘Tumbleweeds’ by Whitman, and each one is a testament to how he changed their lives.

Pia Copper said Whitman hired her on the spot in 1994, and she stayed 10 years.

’He found so many young people who were lost, on drugs, totally hopeless, and they lived here. And there was no hard logic to it, other than: Give them a roof, and maybe part of the shop will rub off on them,’ Copper said.

Though eventually an economic success, attracting book lovers from all over the world and writers such as Anais Nin, Lawrence Durrell, Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the running joke was that the place rarely actually did what a bookstore is supposed to do: Sell books.

And that was exactly how Whitman wanted it. He used to call Shakespeare & Co. ‘a socialist utopia masquerading as a bookshop,’ and in a recent interview with the Los Angeles Times, he said: ‘I never had any money, and never needed it. I’ve been a bum all my life.’

But Whitman was something of a wild-haired, and wild-mannered, king to those who knew him. The land he ruled, with its constant flow of lodgers and poets from all over the world, might as well have come out of the books he loved, and read so voraciously. (One per night.)

Inspired by Sylvia Beach’s famous Paris bookstore and publishing house, which closed during World War II, Whitman fashioned the 17th century, two-story apartment into a labyrinth of soft-lit, teetering bookshelves, winding stairs, a library, stacks of well-read Life magazines, and cushy benches that turned to beds at night for Tumbleweeds. Free tea and pancake brunches were served every weekend to anyone brave, or hungry enough. After brunch, the leftover, mysteriously thick pancake batter was used as glue to repair peeling floor rugs.

Whitman didn’t care much for supervising the young lodgers that passed through, but his temper could famously flare if a book was misplaced or an edition not shelved just so.

’He’s the most un-phony person,’ Sylvia Whitman, 30, said in an interview this year with The Times. He ‘says what he thinks, and he doesn’t care what anyone thinks of him. And it’s quite refreshing.’

He once threw a book out the second floor window at a customer below because he thought they might enjoy reading it. And he used to light people’s hair on fire to save them the trouble of paying for a haircut. After all, he had been using the same technique on himself for years.” [….]

And from the New York Times:

“More than a distributor of books, Mr. Whitman saw himself as patron of a literary haven, above all in the lean years after World War II, and the heir to Sylvia Beach, the founder of the original Shakespeare & Company, the celebrated haunt of Hemingway and James Joyce.

As Mr. Whitman put it, ‘I wanted a bookstore because the book business is the business of life.’

Overlooking the Seine and facing the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, the store, looking somewhat beat-up behind a Dickensian facade and spread over three floors, has been an offbeat mix of open house and literary commune. For decades Mr. Whitman provided food and makeshift beds to young aspiring novelists or writing nomads, often letting them spend a night, a week, or even months living among the crowded shelves and alcoves.

He welcomed visitors with large-print messages on the walls. ‘Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise,’ was one, quoting Yeats. Next to a wishing well at the center of the store, a sign said: ‘Give what you can, take what you need. George.’ By his own estimate, he lodged some 40,000 people.

Mr. Whitman’s store, founded in 1951, has also been a favorite stopover for established authors and poets to read from their work and sign their books. Its visitors list reads like a Who’s Who of American, English, French and Latin American literature: Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, Samuel Beckett and James Baldwin were frequent callers in the early days; other regulars included Lawrence Durrell and the Beat writers William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso, all of them Mr. Whitman’s friends.

Another was the Beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti. The two met in Paris in the late 1940s and discussed the importance of free-thinking bookstores. Mr. Ferlinghetti went on to found what became a landmark bookshop in its own right, City Lights, in San Francisco. Their bookstores would be sister shops, the two men agreed.

Mr. Whitman’s beacon and enduring influence was Walt Whitman (no relation), who also ran a bookstore, more than a century ago. In a pamphlet, Mr. Whitman wrote that he felt a kinship with the poet. ‘Perhaps no man liked so many things and disliked so few as Walt Whitman,’ he wrote, ‘and I at least aspire to the same modest attainment.’” [….]

Addenda: Professor Alice Woolley has kindly informed me of a book that some of us might enjoy: Jeremy Mercer, Time Was Soft There: A Paris Sojourn at Shakespeare & Co. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2005).

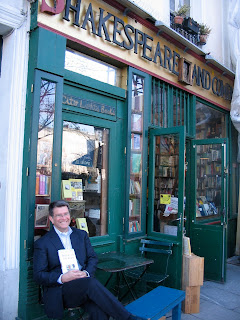

One of my former classmates from high school (class of 1975!), Patrick J. Cain, an attorney in Los Angeles, sent the following picture of himself sitting outside Shakespeare & Co. holding a copy of Father Gregory Boyle’s Tatoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion (2010) which, it turns out, was penned by Patrick’s brother-in-law!

No comments:

Post a Comment