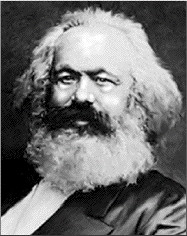

“Once again the time has come to take Marx seriously.”—Eric Hobsbawm, How to Change the World: Reflections on Marx and Marxism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011)

“In the Marxist tradition, self-realisation is the full and free actualisation and externalisation of the powers and the abilities of the individual.” —Jon Elster

“Under suitable conditions, both [political democracy and economic democracy] can be arenas for joint self-realisation.”—Jon Elster

The Capabilities Approach to Human Development

“Considering the various areas of human life in which people move and act, this approach to social justice asks, What does a life worthy of human dignity require? At a bare minimum, an ample threshold level of ten Central Capabilities is required. Given a widely shared understanding of the task of government (namely, that government has the job of making people able to pursue a dignified and minimally flourishing life), it follows that a decent political order must secure to all citizens at least a threshold level of these ten Central Capabilities:

1. Life. Being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length; not dying prematurely, or before one’s life is so reduced as to be not worth living.

2. Bodily health. Being able to have good health, including reproductive health; to be adequately nourished; to have adequate shelter.

3. Bodily integrity. Being able to move freely from place to place; to be secure against violent assault, including sexual assault and domestic violence, having opportunities for sexual satisfaction and for choice in matters of reproduction.

4. Senses, imagination, and thought. Being able to use the senses, to imagine, think, and reason—and to do these things in a ‘truly human’ way, a way informed and cultivated by an adequate education, including, but by no means limited to, literacy and basic mathematical and scientific training. Being able to use imagination and thought in connection with experiencing and producing works and events of one’s own choice, religious, literary, musical, and so forth.

5. Emotions. Being able to have attachments to things and people outside ourselves; to love those who love and care for us, to grieve at their absence; in general, to love, to grieve, to experience longing, gratitude, and justified anger. Not having one’s emotional development blighted by fear and anxiety. (Supporting this capability means supporting forms of human association that can be shown to be crucial to their development.)

6. Practical reason. Being able to form a conception of the good and to engage in critical reflection upon the planning of one’s life. (This entails protection of the liberty of conscience and religious observance.)

7. Affiliation. (A) Being able to live with and toward others, to recognize and show concern for other human beings, to engage in various forms of social interaction; to be able to imagine the situation of another. (Protecting this capability means protecting institutions that constitute and nourish such forms of affiliation, and also protecting the freedom of assembly and political speech.) (B) Having the social bases of self-respect and nonhumiliation; being able to be treated as a dignified being whose worth is equal to that of others. This entails provisions of nondiscrimination on the basis of race, sex, sexual orientation, ethnicity, caste, religion, national origin.

8. Other species. Being able to live with concern for and in relation to animals, plants, and the world of nature.

9. Play. Being able to laugh, to play, to enjoy recreational activities.

10. Control over one’s environment. (A) Political. Being able to participate effectively in political choices that govern one’s life, having the right of political participation, protections of free speech and association. (B) Material. Being able to hold property (both land and movable goods), and having property rights on an equal basis with others; having the right to seek employment on an equal basis with others; having the freedom from unwarranted search and seizure. In work, being able to work as a human being, exercising practical reason and entering into meaningful relationships of mutual recognition with other workers.”—Martha Nussbaum, Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011)

Eleven Criticisms of Capitalism

- Capitalist class relations perpetuate eliminable forms of human suffering.

- Capitalism blocks the universalization of conditions for expansive human flourishing.

- Capitalism perpetuates eliminable deficits in individual freedom and autonomy.

- Capitalism violates liberal egalitarian principles of social justice.

- Capitalism in inefficient in certain critical respects.

- Capitalism has a systematic bias towards consumerism.

- Capitalism is environmentally destructive.

- Capitalist commodification threatens important broadly held values.

- Capitalism in a world of nation-states fuels militarism and imperialism.

- Capitalism corrodes community.

- Capitalism limits democracy.

The Worker as Artist

“We have gone so far as to divorce work from culture, and to think of culture as something to be acquired in hours of leisure; but there can only be a hothouse and unreal culture where itself is not its means; if culture does not show itself in all we make we are not cultured.”—Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

“Industry without art is brutality.”—Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

A Civic Minimum: A Reform Programme

Making work pay: “All those who are expected to satisfy a minimum work expectation must receive a decent minimum income in return for doing so. This includes not only a level of post-tax earnings sufficient to cover a standard set of basic needs, but also a decent minimum of health-care and disability coverage…. The model of a minimum wage combined with in-work benefits for the low-paid, including child-care subsidies for low earners, is certainly one credible approach to this task.”

From a work-test to a participation-test: “Work-tests within the welfare system are…legitimate in principle. But in order that different forms of productive contributions can be treated equitably, social policy must be structured in a way that acknowledges the contributive status of care work. This implies a need to offer some public support for care workers, relieving their need to do paid work to maintain access to the generous basic needs package described above. Relevant policies here might include payment of a decent social wage to those engaged in looking after the elderly or the handicapped on a full-time basis and publicly subsidized paternal leave from paid employment. In other words, access to the generous basic-needs package should be conditional not on satisfying a work-test, narrowly construed in terms of paid employment, but on satisfying a broader participation-test, where participation is understood to include paid employment and (at least in addition) specified forms and amounts of care work.”

Towards a two-tiered income support system: “[T]he debate over ‘welfare reform’ is often polarized between supporters of an unconditional basic income that is not subject to any work- or participation-test, nor to any time limit, and supporters of time-limited workfare. An alternative approach…looks to establish a two-tiered system of income support. The first tier, which we may call conventional welfare, would be contractualist in kind. It would offer support through a mix of income-related and universal benefits, but support that is also linked to, and conditional on, productive contribution. While work- or participation-tested, support at this level would not be time-limited. [….] The second tier might then consist of something like the time-limited basic income…. This would be an additional income grant, not subject to any work- or participation-test, but which would be time-limited. Citizens could trigger the entitlement for a fixed amount of time over the full course of their working lives, but would not enjoy it indefinitely.”

Universal capital-grant or social drawing rights: “[We previously] set out the case for instituting a generous capital endowment as a basic right of economic citizenship. …[A] scheme of universal capital grants might in part incorporate the time-limited basic income mentioned above. Otherwise, the grants could be linked to activities that are related to productive contribution in the community, such as education, training, setting up a business, and, perhaps, care work….

Accessions tax: “[We have also made] the case for heavy taxation of wealth transfers (inheritances, bequests, inter vivos gifts). Such taxation is important to help prevent class inequality and violation of reciprocity. There is a strong case for hypothecating the funds from taxation of wealth transfers to the funding of a universal capital-grant scheme.”

“[T]his short list is not, by any means, exhaustive of the policies and institutions that might be necessary, or helpful, [in order to] reform the terms of economic citizenship so as to meet the demands of fair reciprocity (in its non-ideal form).”—Stuart White, The Civic Minimum: On the Rights and Obligations of Economic Citizenship (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Economic Democracy

“I have argued that economic Democracy, as a system, will be less alienating than Laissez Faire. To summarize the reasons: Workers will have more participatory autonomy under Economic Democracy, because the degree of workplace democracy will not be restricted by the capitalists’ need to keep open all options for profit. The labor-leisure trade-off should be more in accordance with the general interest under Economic Democracy, because workers will have a greater interest in promoting more flexible, less frantic, more meaningful working arrangements, as well as shorter hours and longer vacations, than do capitalists, who bear the costs and risks of such changers (under Laissez Faire) but do not receive the full benefits. Workers are likely to be more skilled under Economic Democracy, because neither competitive pressures nor the need for control will push so hard toward deskilling.”—David Schweickart, Against Capitalism (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996)

America the Possible: The Values

[….] Many thoughtful Americans have concluded that addressing our many challenges will require the rise of a new consciousness, with different values becoming dominant in American culture. For some, it is a spiritual awakening—a transformation of the human heart. For others it is a more intellectual process of coming to see the world anew and deeply embracing the emerging ethic of the environment and the old ethic of what it means to love thy neighbor as thyself. But for all, the possibility of a sustainable and just future will require major cultural change and a reorientation regarding what society values and prizes most highly.In America the Possible, our dominant culture will have shifted, from today to tomorrow, in the following ways:

- from seeing humanity as something apart from nature, transcending and dominating it, to seeing ourselves as part of nature, offspring of its evolutionary process, close kin to wild things, and wholly dependent on its vitality and the finite services it provides;

- from seeing nature in strictly utilitarian terms—humanity’s resource to exploit as it sees fit for economic and other purposes—to seeing the natural world as having intrinsic value independent of people and having rights that create the duty of ecological stewardship;

- from discounting the future, focusing severely on the near term, to taking the long view and recognizing duties to future generations;

- from today’s hyperindividualism and narcissism, and the resulting social isolation, to a powerful sense of community and social solidarity reaching from the local to the cosmopolitan;

- from the glorification of violence, the acceptance of war, and the spreading of hate and invidious divisions to the total abhorrence of these things;

- from materialism and consumerism to the prioritization of personal and family relationships, learning, experiencing nature, spirituality, service, and living within limits;

- from tolerating gross economic, social, and political inequality to demanding a high measure of equality in all these spheres.

Two other key factors in cultural change are leadership and social narrative. Leaders have enormous potential to change minds, and in the process they can change the course of history. And there is some evidence that Americans are ready for another story. Large majorities of Americans, when polled, express disenchantment with today’s lifestyles and offer support for values similar to those urged here.

Another way in which values are changed is through social movements. Social movements are about consciousness raising, and, if successful, they can help usher in a new consciousness—perhaps we are seeing its birth today. When it comes to issues of social justice, peace, and environment, the potential of faith communities is vast as well. Spiritual awakening to new values and new consciousness can also derive from literature, philosophy, and science. Consider, for example, the long tradition of “reverence for life” stretching back over twenty-two hundred years to Emperor Ashoka of India and carried forward by Albert Schweitzer, Aldo Leopold, Thomas Berry, E. O. Wilson, Terry Tempest Williams, and others.

Education, of course, can also contribute enormously to cultural change. Here one should include education in the largest sense, embracing not only formal education but also day-to-day and experiential education as well as the fast-developing field of social marketing. Social marketing has had notable successes in moving people away from bad behaviors such as smoking and drunk driving, and its approaches could be applied to larger cultural change as well.

A major and very hopeful path lies in seeding the landscape with innovative, instructive models. In the United States today, there is a proliferation of innovative models of community revitalization and business enterprise. Local currencies, slow money, state Genuine Progress Indicators, locavorism—these are bringing the future into the present in very concrete ways. These actual models will grow in importance as communities search for visions of how the future should look, and they can change minds—seeing is believing. Cultural transformation won’t be easy, but it’s not impossible either. [….]—From James Gustave Speth’s “America the Possible: A Manifesto, Part II,” Orion magazine (May/June 2012)

Global Justice

“[A]ffluent people in developed countries have duties to respond to globalization with measures that would strengthen developing economies because otherwise they would take advantage of people in developing countries. A person takes advantage of someone if he derives a benefit from her difficulty in advancing her interests in interactions in which both participate, in a process that shows inadequate regard fro the equal moral importance of her interests and her capacity for choice. In the case of globalization, the central difficulties are bargaining weaknesses due to desperate neediness.”

“[M]ajor unmet transnational responsibilities [are located] in two aspects of globalization. The first corresponds to the familiar charge that transnational corporations exploit. In transnational processes of production, trade, and investment, people in developed countries currently take advantage of bargaining weaknesses of individuals desperately seeking work in developing countries, in way that show inadequate appreciation of their interests and capacities for choice. Responding to this moral flaw, a citizen of a developed country ought to use benefits derived from this use of weakness to relieve the underlying neediness. The other aspect corresponds to familiar charges of inequity in the institutional framework that regulates world trade and finance. The multinational arrangements that sustain globalization depend on tainted deliberations in which the governments of developed countries take advantage of the weak capacity to resist their threats of governments of developing countries. Citizens of developed countries should support arrangements that would be the outcome of responsible deliberations based on relevant shared values, a shift that would entail giving up large current advantages to promote the interests of people in developing countries.”—Richard W. Miller, Globalizing Justice: The Ethics of Poverty and Power (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010)

Please note: A couple of earlier (and more historically oriented) posts for May Day are here and here.

No comments:

Post a Comment